(continued from Part 1)

Though Shin Megami Tensei is far from mainstream, it wasn't long into its history that it began experimenting with spinoffs to reach different audiences. Shin Megami Tensei if…’s 1994 release traded nuclear devastation for a high school setting that served as a hub for abstract dungeons and a focus on the eroding psychological health of its villain—a much more intimate subject than previous games, establishing that “the side games… [treated] smaller themes compared to mainline [SMT].” [1] The second major spinoff was 1995’s Devil Summoner, a mix of detective pulp and occult matter which “was kept relatively simple and straightforward so that players could enjoy the story as it unfolded." [2] Though narrower in scope, these spinoffs were still clearly cut from SMT’s cloth.

Of course, there was another spinoff, 1996’s Persona,

which saw the potential of SMT: if...'s high school setting and

psychoanalytical concepts and ran with them. Its very title and central concept

refer to the work of Carl Gustav Jung, famed psychoanalyst, and don’t stop

there: terms like Shadows, Philemon, personas originating from a "sea of

the soul," and many other premises and interpretations derive from Jung's

work. The psych angle was a natural fit for the Megami Tensei franchise, as

Jung is still known for popularizing the psychological interpretation of myths

and the religious experience. What were once gods and monsters physically

manifesting through computers could now be personality-changing

"masks" originating from internal rather than external sources,

without the need of technology.

But it would be naive to say that the creation of Persona

was entirely for the purpose of exploring psychological matters. Kaneko

admits that, compared to the main series, “Persona was geared towards a

younger audience." [2] The switch to casts of high

schoolers and a heavier story and dialogue focus was all about appealing to

different demographics. This turned out to be a seemingly magic formula, as adding

a more relatable human element to Megami Tensei's modern settings paved the way

for the breakout hits of Persona 3 and Persona 4. But what exactly is

behind the popularity of these modern Persona games, and how would their

success impact Atlus and the Shin Megami Tensei series as a whole?

From Fool to Magician

Obviously, Personas 3 and 4 didn't happen overnight. Their

legacy begins with the fact that Shin Megami Tensei's concepts are

malleable and easily suited to any number of scenarios. The creative leads

responsible for molding SMT into its new form were Atlus cornerstone and

producer/director Cozy Okada, writer Tadashi Satomi, and, of course, artist

Kazuma Kaneko. Their talents lead to the creation of the PlayStation's Persona and the Persona

2 duology of Innocent Sin and Eternal Punishment. For Okada,

taking the series back to school was a natural move:

Put simply, given the popularity of the PlayStation with more casual game players, too, we wanted to make a game that they could ease themselves into as well. Like our other games, we're still about making players the actual protagonist in terms of how things proceed, but we tried to make it a bit more of an emotionally approachable game, one that players would be able to more readily relate to. We tried to target a bunch of different potential audiences in making that move, from kids still in school themselves all the way up to working adults who want to go back to that time in their lives and reminisce a little. [3] Pretty much everybody experiences being a student at some point in their lives. It's something everybody can relate to, including myself, and it was a time when we absorbed everything...In that sense, I believe it helps the players to accept the theme and the variety of ideas that we've proposed. [4]

Similar to Shin Megami Tensei and its mythological bent,

psychological themes would be deliberately integrated throughout Persona’s and

Persona 2’s narrative and gameplay, including places of inner meditation like

the Velvet Room, where the player creates new personas. Kaneko speaks proudly of this

first era of Persona games, commenting, "In Persona we

concentrated on the emotional and psychological aspects of the characters so

much that it was comparable to a work of literature." [2] Tadashi

Satomi’s scenario writing would share this ambition, culminating in the

creatively insane Persona 2 duology, which is layered with complex character

relationships. Getting the characters right was of paramount importance

for the fledgling series. Of the first game, Satomi notes, “In terms

of actual narrative content, the thing I worked on most was depicting the

characters' psychology well, especially on an existential level.” [3]

It could be said that the original generation of Persona

titles hewed closer to their JRPG contemporaries than other SMT games, with a

simplified structure though perhaps not simplified content. One of the most

apparent differences is that Persona uses a more typical character-based party

structure: “The Megami Tensei series has traditionally featured the main

character employing demons in his/her party. Persona, in which several main

characters form a party, is actually the one that’s unusual.” [2]

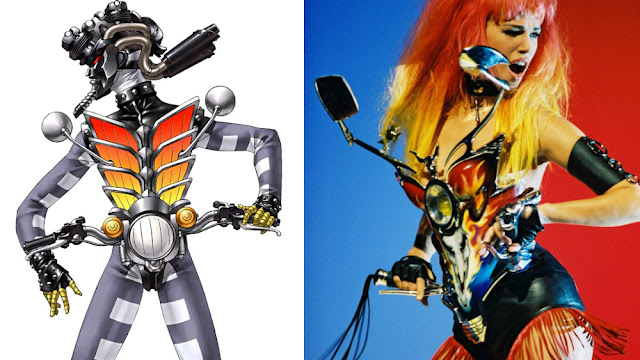

This doesn’t mean demons are completely absent, as they were adapted to fill the roles of the personas summoned in battle by the characters, many using the basics of their mainline SMT designs. However, the personas specifically created for the Persona series have a design aesthetic and rules in contrast to the main series; whereas SMT utilizes the “collective interpretation” of neutrality with its demons, Persona’s personas are designed with a “personal interpretation” that is intended to be reflective of the individual summoning them. Kaneko touches on this difference: “For example, [the design of] Kali follows mythology in the Shin Megami Tensei series, but in Persona 1 I had to redraw features of her costume to prioritize her image.” [5] Particularly in Persona 2, Kaneko’s persona designs have a distinct influence of fashion and haute couture. They no longer resembled gods and demons of traditional art, but more of costumes from a play or runway.

This doesn’t mean demons are completely absent, as they were adapted to fill the roles of the personas summoned in battle by the characters, many using the basics of their mainline SMT designs. However, the personas specifically created for the Persona series have a design aesthetic and rules in contrast to the main series; whereas SMT utilizes the “collective interpretation” of neutrality with its demons, Persona’s personas are designed with a “personal interpretation” that is intended to be reflective of the individual summoning them. Kaneko touches on this difference: “For example, [the design of] Kali follows mythology in the Shin Megami Tensei series, but in Persona 1 I had to redraw features of her costume to prioritize her image.” [5] Particularly in Persona 2, Kaneko’s persona designs have a distinct influence of fashion and haute couture. They no longer resembled gods and demons of traditional art, but more of costumes from a play or runway.

Evidence suggests that Atlus’ experiment of audience

outreach was successful, by the company’s modest standards. In Japan, Persona moved 391,556 units, [6] Persona 2: Innocent Sin

reached 274,798 lifetime, [7] and Persona 2: Eternal Punishment

sold 200,103. [8] Persona’s more grounded settings and strong characters

surely helped it win over players who wouldn't otherwise be interested in

apocalyptic doom and gloom.

From Hanged Man to Death

A new era would await Atlus on the PlayStation 2. After

focusing on spinoff titles for nearly a decade, Atlus returned its sights to

the SMT main series in 2003 with Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne.

A true paradigm shift, Nocturne brought the series’ presentation and

gameplay into the 21st century and gave Atlus an engine framework

from which to iterate further PS2 titles. Nocturne sold 245,520 copies

in Japan [9]; its expanded re-release, SMTIII: Nocturne Maniacs,

sold 77,791. [10] However, Cozy Okada, who, beyond his creative roles,

was one of Atlus’ founders, departed the company in late 2003. Why he left is

unknown, though it possibly had to do with the failure of the half-baked Shin

Megami Tensei: NINE, the ambitious (read: expensive) Nocturne not

meeting sales projections, or other internal strife that will never be made

public. Okada subsequently formed an independent studio, Gaia, which developed

two SMT clones before shuttering in 2010. [11]

For Atlus, the three years after Okada’s departure would

turn out to be a transitional period. 2004 would see the SMT mainline series' first international

release when SMTIII was released in North America in October of that

year, under the name Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne. 2004 would also see

another major release in Japan, the Tadashi Satomi-penned Digital Devil Saga

duology, with its second half releasing in 2005; both would be released in

North America in 2005, the beginning of a consistent trend for Atlus USA's

localization process. However, even though Digital Devil Saga was the

most Final Fantasy-like Megami Tensei product yet, evident in its colorful cast

and straightforward character-based progression trees, its sales disappointed. Year-end sales in Japan for 2004 peg Digital Devil Saga

at a modest 153,421 [10]; only 90,812 [12] returned for Digital

Devil Saga 2 in 2005. The 2006 revival of the Devil Summoner series, Raidou

Kuzunoha vs. the Soulless Army, only managed 91,008. [13]

Amid these lagging sales, 2006 also saw the Japanese release

of Persona 3, a game that remixed ideas and assets from Nocturne and previous Persona titles to different aims, under the auspices of the

younger Atlus staff. Names like director Katsura Hashino, designer Shigenori

Soejima, and composer Shoji Meguro would be the new creative leads. The members

of the "old guard" like Tadashi Satomi would disappear into the ether

that claimed Cozy Okada, while Kaneko himself elected not to have direct involvement

in this new project:

Kaneko: I wanted to let the newer, younger staff grow and gain experience. I tried not to, you know, push my own view or anything on Persona. That's because there's the sort of fan that likes the dark, colder atmosphere of the core [Shin Megami Tensei] series--Persona's a lot lighter.Kaneko: Yes, exactly. And that's where I want Persona to be...for a wider audience to appreciate Megami Tensei. It's like a separate branch. I'd like to make it more distinguished by having someone other than myself working on it. [14]

The fresh faces: from left, Katsura Hashino, Shigenori Soejima, Shoji Meguro

Persona 3 was a watershed moment for the company and

the franchise, with sales of around 210,319 for the year. [13] While

that's less than what Nocturne or the original Persona sold, this

new generation of Persona was only getting started; Persona 4, released

two years later in 2008, sold 294,214, [15] and truly ignited the

Persona phenomenon. Effectively going back to the Megami Tensei drawing board with

a fresh perspective, Persona 3's and Persona 4's departures from

other games in the franchise and keen insight on contemporary trends in

Japanese gaming were at the root of their successes. So what were the innovations

that catapulted P3 and P4 to a level of recognition the other

games of the franchise could not reach?

1. Primary Focus on Characters and Relationships. Primacy

of character interaction was certainly nothing new to RPGs or the Persona

series, but Personas 3&4 introduced a significant innovation: Social

Links. Though the crux of Social Links, relationship vignettes between the

protagonist and other characters, is undeniably similar to preceding concepts

like the Tales series’ skits or aspects of PC dating simulators, P3&4’s

vital development was to quantify a relationship into levels. These levels, or

“S. Link Ranks,” offer incrementally rising experience bonuses for persona

fusion and thus expedite the battle and dungeon-crawling process, so increasing

S. Link Ranks as high as possible (up to a max of Rank 10) becomes a priority

for the player. However, most of their content is separate from the main

storyline: "the Social Links the Hero establishes with people are a

reflection of that [protagonist's] personal values and philosophy, and do not

necessarily hold any particular meaning over the rest of the game." [16]

What was once character growth available in other RPGs only through specific

sidequests was now integrally tied to a positive feedback loop that could only

benefit the player, except in the rare case of an easily mended relationship

reversal.

|

| Character relationships affect P3&4's major gameplay systems |

An extra aspect of Social Links is the ability to romance

classmates. A reward for successfully completing a Social Link sequence with

peers of the opposite sex, these romances have almost zero impact elsewhere in

the storyline but have added significantly to the allure of P3&4, particularly

in overseas markets where such features are uncommon on console games. In an anecdote, director

Hashino notes how during early development of Persona 3, a menu-based, visually

minimal Social Link simulation still managed to enrapture staff members with

this possibility: "One of the most unusual things I heard about from

the staff when gathering their thoughts about this simulator was how fun it

suddenly was once a character became your lover! Even with no visuals to go

along with the Social Link and nothing but dialog boxes to work off of, somehow

that allure you feel around the opposite sex as a young adult like in the game

still somehow came through! As a result of all that, this simulator was

indispensable to us as we were working on the feel of the calendar system and

it somehow made Social Links with the girls in the game even more satisfying

than we originally envisioned." [17] Considering their myriad intrinsic

rewards, it's no surprise that Social Links have become one of modern Persona’s

most popular features.

The way P3&4 present their S. Links and story

sequences—static

camera angles, large portraits and text boxes, and character models that

puppet

dialogue cues—is a considerable step back from the dynamic, cinematic

cutscenes

of Nocturne and Digital Devil Saga, essentially resembling

PlayStation-era RPGs.

While this presentation style is flexible, it also runs the risk of

cutscenes

being interminable or containing repetitious dialogue, and certainly

neither P3

nor P4 is immune from either. But considering the games’ length and

their

abundance of dialogue, it’s a pragmatic approach that doesn’t eat up

budget that can be expended elsewhere, such as the animated cutscenes

interspersed rarely throughout both games. And, at least in Japan, the

preponderance of visual novels and their aesthetic influence on many

modern RPGs means

that the intended audience has a built-in acceptance of this style.

|

| Nocturne's cinematics were impressive, but to replicate the same effect with P3&4's copious interactions would have been unfeasible |

Despite a greater focus on dialogue and characters than

either the mainline Shin Megami Tensei series or previous Persona games,

P3&4 do not possess plots anywhere near the density of the Persona 2

duology and are instead a better match for the comparatively straightforward,

though not necessarily simple, initial Persona title. This is not necessarily a weakness

and instead may be an inevitable effect of how P3&4 are structured,

unfolding day by day and never without your posse of friends to discuss

important events in detail. But even without overwhelming complexity, both

games possess strong central themes and twisting turns such as deducing the

identity of Persona 4’s murderer.

2. An Entertaining Tone. Persona has never been as

serious in tone as the main SMT series, but P3&4 are seemingly cognizant of

their own fiction, with tonal shifts that swing from absurd to serious over

short periods. Even though both games feature supernatural elements pecking

away at the fringes of the real world, these extreme circumstances do not

preclude fun trips to hot springs, or the male characters trying to peer at

girls on the beach after one experienced personal trauma the night before. Mascot characters like Teddie, who try to inject most moments with

humor, would seem out-of-place in Shin Megami Tensei, but are easily accepted

within the timbre of Persona. Above all, it's apparent that modern Persona knows

its target audience just wants to have fun: "An important

characteristic of the Persona series is that it’s a 'young-adult fiction' work."

[18]

3. New Art Style. With Kaneko bowing out of the Persona

series, the torch of art designer was passed onto Shigenori Soejima, who, up until

Persona 3, was most notable for adapting Kaneko’s art into character portraits

for the previous Persona and Devil Summoner games. "Naturally, [Kaneko]

had a large influence on me, since I was his assistant for a long time. So when

I approached the designs [in P3&4], I thought I didn't need to consciously

emulate his style, and if I explored what my own strengths were instead, I

could come up with something new." [19] Even if the approach

was his own, Soejima’s persona designs are nonetheless a close match for

the style and rules Kaneko set for himself with Personas 1 and 2; his human

characters, though less distinct from industry standards compared to Kaneko’s, still

possessed the series' fashionable qualities.

In addition, Persona 3 began a trend of utilizing theme

colors to paint mood or tone into the menu aesthetics and overall visual

design. "When I work on a title, its theme color is very important to

me. I think when a person remembers things unconsciously, what leaves the

strongest impression isn't words or shape, but color. P3's theme color, blue,

symbolizes adolescence; P4's yellow is the color of happiness. Both meanings

are tied to Japanese culture, so it might be hard for western audiences to

understand." [19] The sleek style resulting from bold colors has become characteristic of Persona.

4. Use of Vocal Music. Like Soejima, composer Shoji

Meguro joined Atlus in the mid-90s as they were developing their audience

expanding games like Devil Summoner and Persona. In his own words, he felt

constricted by the technical limitations set by console hardware in reproducing

his music: "In Digital Devil Saga, we could use streaming to play about

half the songs. And in P3 and Devil Summoner: Raidou Kuzunoha vs. the Soulless

Army, all the songs were streamed. That was the point at which I was finally

able to express my music without making any compromises, and I felt that I made

it to the starting line." [19] Once the PlayStation 2 and DVD

format permitted CD-quality music in needed amounts, he was free to compose how

he wanted. In Persona 3 (and continuing since), this resulted in numerous vocal

tracks, used in a variety of situations throughout the game.

|

| Meguro shredding at a Persona concert |

While vocal music is nothing new to video games—proper songs

have been heard in games since CD-ROMs emerged as a storage medium, usually

in opening movies or the ending credits—what was different in P3&4 was

where it was heard. Whether in battle, cruising the town, or hanging out after

school, Meguro’s typically Japanese-pop-infused tracks broke the mold of the

standard orchestral scores heard in other RPGs. And since these games are so

long, chances are the lyrics, unintelligible “Engrish” as they may be, will get

stuck in your head whether you like it or not. It seems to have paid off for

Meguro and Atlus, as frequent P3&4 soundtrack releases and remixes have become the norm, not

to mention the yearly live Persona concerts headlined by Meguro himself

and played in established venues like Tokyo’s Budokan.

5. Economy of Authentic Settings. While Personas 1 and 2 starred

high school students, not a lot of time was actually spent in high schools or

doing high schooler things. Once the setting was established, the young heroes were

swept up into the story’s events like so many other stoic protagonists seen in

Japanese RPGs. But in Personas 3&4, high school is the central location.

Nearly every day of the calendar defaults to school-based activities like

hearing rumors on the way to school, listening to short blurbs from teachers,

encountering friends between classes, or taking tests. It’s also a hub for

Social Link interactions, some of which are explicitly tied to the school, like

those involving school clubs and extracurricular activities. Outside of the

school life, a handful of other areas like malls or shrines add to the

authenticity of the Japanese setting while providing more avenues for Social

Links. According to Hashino, the limited number of locations meant that "the

cost of creating the environment was lower than the standard in RPG

development, allowing us to expand other portions of the game. And staying in

the same location in the perfect way to allow the players to sympathize with

the daily life that passes in the game." [19]

But when they do appear in P1&2, high schools are little

more than traditional RPG dungeons with a modern coat of paint; it was merely

novel at that time to navigate mazes intended to be something other than the

customary moldy crypts or haunted castles. And though P1&2 staged their

conflicts in varied locations like hospitals and record stores, P3&4

simplified this by each having a singular, clearly delineated “shadow world”

where the actual battles and persona mechanics finally come into play. While

they are relatively simple-looking—each shadow world has mostly procedurally

generated layouts with basic tileset patterns—both Persona 3’s Tartarus and

Persona 4’s Midnight Channel tie into the thematics of their respective games. Tartarus is literally even a nightmare version of P3’s school, makes it

apparent that, even if separated by gameplay mechanics or story delineations, high

school remains the axis mundi of the modern Persona experience.

6. Time Management and Life Simulation. Nearly all RPGs,

Shin Megami Tensei and previous Persona games included, are strictly paced via

“event flags,” which are simple, usually time-unconstrained triggers that progress

the game, like talking to a specific NPC or defeating a boss. Personas 3&4 would

mostly turn this convention on its head with the introduction of a time

management system where the player, living vicariously through the protagonist,

experiences life one day at a time over the course of nearly a year. In the initial

plan for Persona 3, its scenario involved living through all three standard years

of Japanese high school, but was trimmed down to one for players’

considerations. [17] The calendar year introduces a key element of life

simulation, as during the year responsibilities (i.e., school, plot demands)

must be juggled daily with the joys of free time (Social Links). This time/calendar

system Hashino calls along with Social Links “some of the most drastic

gameplay changes we’ve ever implemented.” [17]

The impetus for this time system was to “replicate

through gameplay the sensation of having a day-to-day life, one that includes actual

weekdays and weekends. The sense of fun you get over the course of a single

week can change depending on what sorts of plans you make and how your goals

are coming along. We figured that if players could get a taste of that sort of

sensation through a game that we’d be on to something enjoyable and that’s how

the calendar system came to be.” [17] The innovation of this system

compared to other RPGs is that progress, as measured by the advancing calendar,

is always being made.

|

| Social Links are designed to improve battle efficiency, which then improves time management efficiency, which then improves Social Link management, which then... |

Unfortunately, the calendar is not completely open-ended, as

at prescribed times the plots of both games will dictate that event flag bosses

and dungeons be completed by a certain day to bypass sometimes arbitrary

gating; however, the deadlines are usually made clear. But it’s apparent that

modern Persona treats its combat underbelly as “work,” opposed to the “play”

inherent in Social Links, when it is most rewarding in terms of time management

to spend minimal time in dungeons (or completing them in one fell swoop),

leaving the maximum time for the life simulation aspects of the socially

central “real world.” Proper time management means an increased

quality of life for both player and protagonist.

7. Streamlining of Legacy Systems. For Personas 3&4,

nothing was sacred; if vestigial elements from Shin Megami Tensei or previous

Persona games did not support their collective ambitions, they would either be

refitted or thrown out completely.

Examples of modified concepts include the Press Turn system

and fusion. Nocturne’s innovative Press Turn system provided a model of

benefiting battle gameplay through weakness exploitation for almost all Megami

Tensei games that followed, and in P3&4 it was stripped down to the bare

essentials. Whereas Nocturne doled out extra turns for keen offense or

forfeited enemy turns for impenetrable defense, P3&4’s variant shunned the

extra turns and defensive benefits for an offensive-oriented style of play with

“All-Out Attacks,” powerful unblockable attacks that are a reward for hitting

all weaknesses of the enemy party.

Previously important elements that were removed in Personas

3&4 include demons as battle antagonists and their related conversation

systems. Kaneko-designed demons would now exclusively play the role of the

protagonist’s personas, introducing Soejima’s “Shadows” to the limelight. These

Shadows serve exclusively as one-dimensional “enemies” in the usual RPG sense;

without conversation as an alternate means of battle resolution, the Shadows’

entire purpose is to be defeated—only the handful of boss Shadows are afforded

any plot focus.

|

| Shadows represent little more than their tarot designation |

|

| Persona cards are gained at regular intervals, encouraging frequent fusion |

Judgement

As a sum of these reworked parts, the new face of

Persona

has become an unprecedented success for Atlus, both in Japan and abroad.

This success was not just in sales but also in total brand awareness,

moving

Persona out of the niche that Shin Megami Tensei had been living in for

more

than a decade. The influence of Persona 3 and Persona 4 has without a

doubt

changed the playing field of modern Japanese RPGs, a claim easily

substantiated

by the number of imitators left in their wake. Whether or not Persona was truly at the forefront, trending elements in

Japanese

RPGs released since include high school or academy settings (Valkyria

Chronicles 2, Final Fantasy Type-0), vocal music in gameplay contexts

(Final

Fantasy XIII-2, NieR), and Social Like-style relationship

quantification

(Conception). Other games, like Mind Zero, are total ripoffs.

The triumph of Personas 3&4 is even more

remarkable when

you consider the context and climate of their releases. For Persona 4 in

particular, it became a breakout hit despite it being a

PlayStation 2

game released in 2008, then already years into the subsequent console

generation. However, the continued popularity of the series in the 2010s

has

been especially striking. In Japan, this has been the decade of

burgeoning

mobile development, whose overwhelming share of the market has

cannibalized

many landmark developers, like Irem or even Konami (whose revenue mostly

comes

from non-gaming sectors). In America, this was a time of growing

suspicion or

distaste for Japanese games, particularly RPGs, with the middling

reception of

2010’s Final Fantasy XIII perceived as proof of a genre's obsolescence. But despite these circumstances, Persona has only

blossomed in Japan and P3&4 proved to be critical darlings in the

American press.

So why could Persona breakthrough to mainstream attention

while Shin Megami Tensei could not? Besides the progressive changes listed

above, it's mainly a matter of tone and focus. From SMT's bleak settings to its

meticulous attention to mythological details, it's pretty much the opposite of Persona’s

carefree optimism, despite the series’ shared assets. Where this is most

obvious is in each series' contrasting approach to party members: SMT features

an interchangeable roster of strange "monsters" that don't feature

any character beyond the archetypal personality they're allotted, while Persona

has a more standard cast of friends and fellows who stay and grow along with

the protagonist. It should go without saying that a character defined by a love

of steak or a father complex is going to be more generally palatable than a

stoic god so obscure it might not even have a Wikipedia page. The "human element" is important in order to resonate with an audience, and it's something that's simply stronger in Persona than SMT.

Between its down-to-earth characters and relationships,

being relatable is at the core of Persona’s popularity, which has approached

levels of comparison with other RPG goliaths. It’s not uncommon for Persona 3, especially,

to be compared to Final Fantasy VII, not because it approached that game’s

multi-million sales but for introducing so many players to the Megami Tensei

series who otherwise overlooked Nocturne or Digital Devil Saga. But this

comparison to Final Fantasy is salient; as one of Persona’s founding principles

was to reach a larger audience, P3&4 in particular were not afraid to lean

on the orthodox approaches that SMT opposed. Knowing how important the essence

of “character” is to Persona, perhaps the better analogues are Persona 3 to

Final Fantasy VI and Persona 4 to Final Fantasy VII. Consider the following

comparisons:

- In Persona 3/Final Fantasy VI, you are thrust among a ragtag team, one a carefree young lad whose main arc is defined by the death of his bedridden love interest (Junpei/Locke), a young woman with daddy issues (Yukari/Terra), a cold young woman of authority who is eventually encumbered with great responsibility (Mitsuru/Celes), a non-human who struggles to fit in with the others (Aigis/Terra), a bruiser of a lad with a brotherly relationship (Akihiko/Sabin), an animal (Koromaru/Mog), a little kid (Ken/Relm), and a guy who is in the party briefly and then dies (Leo/Shinjiro); this team opposes an insane megalomaniac (Ikutsuki/Kefka), even deities (Nyx Avatar/Warring Triad).

- Persona 4/Final Fantasy VII feature a central villain (Adachi/Sephiroth) whose shadow you chase the whole game but turns out to be manipulated by a supernatural female force (Jenova/Izanami), a mascot character (Cait Sith/Teddie), a young woman martial artist with an inferiority complex (Chie/Tifa), a guy with a tough-as-nails exterior but a tender center (Kanji/Cid), an endlessly high-spirited lass (Rise/Aeris), and a few more lesser correspondences.

|

| For veteran players, P3's and P4's characters may seem stale and their emotional climaxes cliché |

The World

For these many reasons, the Persona series now possesses the

same kind of impassioned fanbase that Final Fantasy held only a couple

console generations ago. Whereas Final Fantasy’s various missteps over the past decade

have entrenched an air of cynicism among its fanbase and the mainstream gaming

audience it once attracted, Persona now reigns as probably the most genuinely

liked Japanese RPG series of the 2010s, its ragtag parties scratching the persistent itch for a traditional, turn-based,

character-driven RPG experience. Persona has won over hearts like mainline SMT

could only dream of.

|

| One looked better and sold better, but which one found near universal acclaim? |

So if Persona is the new Final Fantasy and if, by Kaneko’s

admission, Shin Megami Tensei exists to be the converse of trends, are the two

series diametrically opposed to one another? Despite the fact that what’s made

Persona into a hot property and what defines SMT are apples and oranges, this

isn’t necessarily true. Persona and SMT live as two sides of a coin; their

strange symbiotic relationship works because each has a discrete identity.

While you could make a post-apocalyptic Persona or a SMT with life sim

mechanics or chatty mascot characters, it would betray the appeal and

individuality of both series. The obvious fact is that Persona’s fresher

outlook and casts of human characters will always garner more attention than

the dourer SMT, particularly from the key demographic of younger players. But

for veteran RPG players who may find modern Persona’s charms to be less unique,

having encountered similar characters in Final Fantasy or elsewhere, Shin

Megami Tensei’s role as an alternate choice from the norm remains as important

as ever.

That said, Persona has subsumed the main series not just in

popularity but in perception. Some effects of this are natural, such as people

thinking that Kaneko’s original demon designs originated from P3&4, the

only games in the series they've played. Then there are instances where the main series is simply perceived as

the inferior product. After all, the cost of being niche is lower sales and

lower budget; this is no problem for most fans because Kaneko's distinct art

style shines through even the most egregious asset reuse, but it may still seem

"cheap" or outright unappealing to the many.

This faces Shin Megami Tensei with a sobering reality: while

remaining one of Atlus' most valuable assets, that also means it is merely a

company's intellectual property and must perform adequately. Too important for

Atlus to shelve entirely, yet facing dwindling returns compared to the Persona

behemoth, something of Shin Megami Tensei had to give. Unfortunately, the core

aspects of SMT that distinguish itself from other games—myth, art style, obtuse

mechanics, alignment characterization—also lack broad appeal and could be

considered expendable in appealing to younger and wider markets. Shin Megami

Tensei's identity as an artwork is unmistakable, but art is trumped by its role

as a consumer product. Could the series transcend its niche without

compromising its distinct identity?

In 2013, this question would receive its answer: Shin Megami Tensei IV.

Next: False Reincarnation

In 2013, this question would receive its answer: Shin Megami Tensei IV.

Next: False Reincarnation

____________________________________________________

References:

[1] Dengeki Online. Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne interview.

[2] 1UP.com. (archived on Megatengaku) Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne.

[3] A Roundtable Interview with Cozy Okada, Tadashi Satomi, and Kazuma Kaneko.

[4] Persona 2: Eternal Punishment Bonus Disc. Kazuma Kaneko and Cozy Okada Interview.

[5] Kazuma Kaneko Works III. Interview.

[6] Geimin.net. Famitsu's 100 Bestselling Games of 1996.

[7] Geimin.net. Famitsu's 100 Bestselling Games of 1999.

[8] Geimin.net. Famitsu's 100 Bestselling Games of 2000.

[9] Geimin.net. Famitsu's 100 Bestselling Games of 2003.

[10] Geimin.net. Famitsu's 100 Bestselling Games of 2004.

[11] Siliconera.com. Gaia, Cozy Okada's Studio, Is...Gone?

[12] Geimin.net. Famitsu's 100 Bestselling Games of 2005.

[13] Geimin.net. Famitsu's 100 Bestselling Games of 2006.

[14] Otaku USA. An Interview with Kazuma Kaneko.

[15] Geimin.net. Famitsu's 100 Bestselling Games of 2008.

[16] Persona 3 Official Design Works. Interview with Creators About Death and Ties.

[17] Creator Works: December 20, 2007, Katsura Hashino, Volume 24.

[18] 1UP.com. (archived on Megatengaku) Persona 4 Afterthoughts.

Excellent articles, thanks for taking the time to write them.

ReplyDelete